What happens when a passive house goes solar?

The goals of passive building are to increase comfort, create a healthy indoor environment, make a durable and resilient structure, and use far less energy than the norm. Well, even the most efficient building uses some energy, it has to come from somewhere, and there are multiple options. What makes the most sense for a house these days? And can solar play a viable role? How would that work for a passive house like mine?

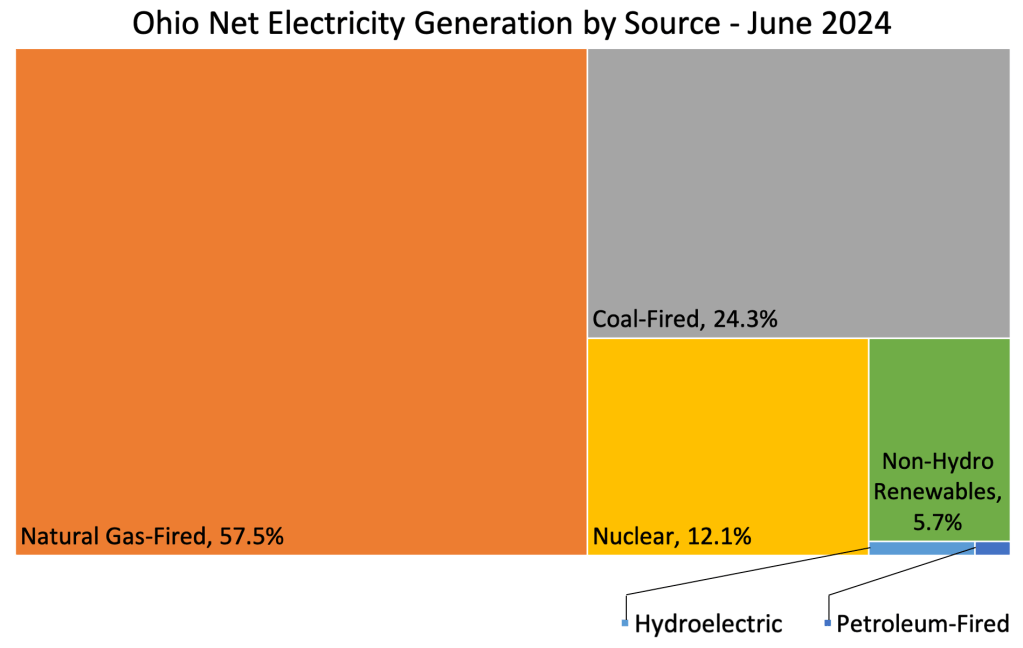

Our Ohio Electrical Grid

Gas is cheap for heating, but it produces air pollutants that can cause serious problems if something goes wrong. True fact—I’ve lived in two small towns in different states that each had a case of deaths by carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning at major chain hotels while I was living there. CO is serious, and it’s a by-product of burning fuel. Even if an appliance is operating correctly, poor or incorrect ventilation in a building can cause dangerous back-drafting of exhaust gases that can expose occupants to this odorless, poison gas.

I like that an all-electric home eliminates this risk. An added benefit is that I don’t have to pay the $40 or so every month just for the privilege of being connected to the gas utility, even when I’m using only $12 worth of gas during summer months. Electricity can be cost-competitive for heating too, if it’s used to power a heat pump. Clintonville Passive House is an all-electric home, meaning there’s no gas used on site for cooking, no wood or propane or oil burned for heat. Everything inside that uses energy is connected to the electrical grid for power.

Right now in Ohio our grid uses several sources of energy to create the electricity that’s delivered to our homes and businesses. According to the US Energy Information Administration, that mix looks something like this:

That means that if I’m connected to the grid my house isn’t really all-electric after all, just as a shiny new electric car operated in the state of Ohio will also be running primarily on natural gas (albeit with greater efficiency due to drivetrain differences from internal combustion vehicles). But that’s not all. There are sources of inefficiency and loss all along the path from generation to final use on site. And that means that every kilowatt-hour I use at the electrical outlet actually takes about two kilowatt-hours’ worth of gas, coal, or nuclear source energy. Awww, man! That’s an awful lot of carbon dioxide and other pollution for an all-electric house. Not to mention my local electric utility has a pesky tendency of asking me for money on a regular basis in exchange for that energy.

Well, if I want my house to be powered by emissions free1 electricity and at a lower price long-term, then it looks like I’ll have to do it myself. What else is new. So, how to go about it?

Designing for a Solar Array

From the outset of this project, I had been planning for on-site solar panels to power the house. Here’s how. To start with, my lot runs north-south lengthwise, and so the front facade of the house is aligned with the predominant direction of the shining sun, which for the northern hemisphere is South.

To take advantage of this, I designed the roof to have a large surface area facing directly south and tilted it upward at an angle that’s pretty darn close to maximizing solar energy collection. My solar roof is a 6:12 pitch, meaning it’s tilted 26.6° from horizontal—very close to the approximately 30° that’s ideal for fixed-angle panels at our latitude.

One benefit of having to do an in-depth, intricate energy model for the house before building it is that I knew upfront about how much energy the house would require, which is just a hair under 10,000 kWh per year. I then made sure to size the south-facing roof to be able to accommodate an array at least the size that can crank out that much energy in a typical year. It turns out that’s 18 panels for Clintonville Passive House.

(Not-so-fun-fact: when I originally sized this roof for solar, I didn’t leave space for a potential 3-foot wide “fire walkway” that’s sometimes required. I also didn’t leave much margin in the case my projected energy use went up a little with further design revisions—which it did. Luckily, the fire walkways aren’t a code requirement in all places, and they weren’t for me. And I just barely was able to squeeze enough panels onto the one roof surface to cover all my energy use. Barely. My word of advice is to plan for enough room for the fire walkways on one side and above the array. Then, create enough available roof area with good sun exposure to produce up to 120% of your projected needs. That’s the most that many utilities will let you have anyway.)

The final decision was to install a standing seam metal roof. That’s not only a great choice as a highly durable, long-lasting roof in its own right. It also provides vertical ribs to attach photovoltaic equipment to without any penetrations through the roof I worked so hard to keep weather-tight.

Batteries or No?

The catch is that the sun is only available between sunrise and sunset. And clouds conspire at largely unpredictable times to substantially shade my panels. Not to mention that although I know about how much energy I’ll need in a year, I don’t really have much of a clue exactly when I’ll need it. There’s no way my power needs are going to precisely equal my solar array’s output at any given minute. And for damn sure I’ll need some energy at 2 am overnight in early February when it’s 3°F outside and hasn’t broken out of the single digits for days. This whole solar thing is feeling tenuous at best. What to do?

Three choices: 1. buy a ton of batteries to be able to disconnect from the electrical grid entirely, aka “go off grid”, 2. buy a few batteries—enough to store energy to ride out a day or two at a time with low sunlight while still being connected to the grid, or 3. be grid-tied with no batteries.

The first option is appealing from the standpoint of being totally independent from the disruption-prone power grid. But it’s crazy expensive and completely unnecessary until I decide to pursue my alternative life dream as a mountain man hermit. The second option—grid-tied with some battery storage—would leave me connected to the grid but still able to rely mostly on my own solar energy.

But that last option sounds easiest, and cheapest too. I’d remain connected to the grid but with an altered electric meter that allows me to sell my surplus power back to the utility for distribution to others who need it at any given time. And when it’s not sunny and I need more power than my panels can produce, I just buy some from the utility instead of needing to store it in expensive batteries. That’s the ticket. I could still have the option in the future to connect an electric vehicle to my home’s electrical panel through a two-way car charger that would allow the car to act as a generator for the house—or possibly even rent it out as energy storage for the grid. But that’s for later consideration.

The best part is that even though my power demand will rarely match my on-site generation level at any given moment, my total energy consumed will be almost exactly equal to the total energy my house produces over any 365 day period. That’s net zero energy. I’m not always going to be the one who will use the energy I produce. And sometimes I’ll need to borrow energy from the grid. But all the energy this house needs will be offset by its own energy production.

Once I’ve had the system running and connected to the grid for a while, I’ll give some periodic updates on system performance. I’m very interested to see how well my actual use and generation figures line up with my estimates. Details aside, I’m absolutely confident that the choice to make CPH all-electric with rooftop solar was right.

Have any of you gone through the process of installing a solar array at your house? Or even designed a house for solar from the outset? What was the process like? I’d love to hear about your challenges and successes.

Until then, let there be light!

Footnotes

- While solar photovoltaics do indeed produce electricity with no emissions at the source, it bears noting that this does not mean there are no emissions of any kind. From embodied energy and carbon dioxide emission from manufacturing of the panels and other equipment, to hazardous chemicals used in their manufacture, and issues surrounding the mining of raw materials, there is a decidedly negative environmental impact from photovoltaics. Still better than the conventional alternatives, though.2

US Energy Information Administration (2024) – “Ohio – State Profile and Energy Estimates” Published online at EIA.gov. Retrieved from: ‘https://www.eia.gov/state/?sid=OH#tabs-4’ [Online Resource] ↩︎

2. Life cycle assessments by NREL show that the greenhouse gas emissions of solar photovoltaics are in the neighborhood of about 4% as much as with coal-fired production per unit of energy produced. Although there are still other environmental and social factors involved3, that’s a huge difference.

NREL (2012) – “Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Solar Photovoltaics” Published online at NREL.gov. Retrieved from: ‘https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy13osti/56487.pdf’ [Online Resource]

3. Another footnote on a footnote? This is getting silly. But please allow it as my syntactically absurd way of making the point that there is a lot to consider. “Our World in Data” has troves of information on estimates of deaths related to different sources of energy production. Their analysis shows that solar is not only among the cleanest but is the safest, resulting in far fewer vocational deaths and accidents as well as health-related deaths among the public. In fact, there are over 1000 times more deaths stemming from coal generation than from solar worldwide per unit of energy produced by each. Wow.

Hannah Ritchie (2020) – “What are the safest and cleanest sources of energy?” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: ‘https://ourworldindata.org/safest-sources-of-energy’ [Online Resource]

Leave a comment